If you bring up the Resident Evil franchise to somebody my age, they’ll often tell you about their first time playing the original RE on PlayStation. The story usually involves a friend’s house, a sleepover, and parents with a more relaxed attitude towards violent video games than their own. They’ll tell you about how scared they were when the zombie dogs (Cerberuses) burst through the windows in the hallway and the stress they felt while watching the doors slowly open on each loading screen. They’ll recall the blood and gore. And if they’ve kept up on video game memes, they’ll throw in a “Jill sandwich” joke for good measure.

My memories of the franchise’s roots are fuzzier. I might have played a bit of Resident Evil in the 90s on a friend’s PlayStation, but if I did, memories of playing Metal Gear Solid would have greatly overshadowed them. At some point in my teenage years, I became more aware of the franchise, but it never caught my interest until I rented Resident Evil: Code Veronica X on a whim for my PS2. I wouldn’t touch the original until sometime after playing its remake on the Nintendo GameCube. It makes sense, though. In my youth, I was undoubtedly a big fan of horror, but I was primarily drawn to psychological horror and ghost stories, never really interested in zombies, slashers, and the accompanied blood and guts.

While my early history with the franchise isn’t as dramatic or exciting as most, I think the context is essential as I dive back into the original, its sequels, remakes, and spinoffs. As I alluded to in my retrospective introduction, I fell backward into becoming a Resident Evil fan, and this blog series is, in part, an exploration of that.

I’m pretty sure the last time I played the original Resident Evil was 18 years ago. And I do mean played. Before starting this project, I hadn’t so much as launched it since beating it back in college. Of course, I remember the legendarily bad live-action introduction, the voice acting, and basic story beats, but the GameCube remake overshadows any memories I have of the original’s structure, puzzles, and gameplay. Diving back into it after all of these years felt fresh and surprising. Almost like playing the game for the first time.

Welcome to REvisited: A Resident Evil Retrospective, an Exposition Break series that explores the highs and lows of the Resident Evil franchise as we go back and replay the mainline games, their remakes, and their spinoffs. If you haven’t already, we encourage you to check out the series introduction to learn more about this project.

Alright, the setup. The year is 1998. Bravo Team, a group of super cops from S.T.A.R.S., the Raccoon City Police Department’s Special Tactics And Rescue Service, has been dispatched to investigate a series of gruesome murders in the city’s outskirts. This groups stops returning R.C.P.D.’s calls and Alpha Team, another group of super cops from S.T.A.R.S., is dispatched to find out what the heck happened to them. Chris Redfield, Jill Valentine, Barry Burton, Joseph Frost, Brad Vickers, and Albert “I Wear My Sunglasses at Night” Wesker arrive on the scene and find Bravo Team’s abandoned helicopter. While investigating the area, Joseph gets attacked and killed by a bloodthirsty dog. Alpha’s pilot, Brad, takes off and flees, abandoning the team. More dogs begin to chase the rest of Alpha through the forest, eventually driving them into the “safety” of a spooky old mansion.

If you’ve never seen the game’s intro, do yourself a favor and check it out. The performances throughout are legendary. It’s a lot of fun. If you’re curious how the glorious mess came together, I recommend you check out Resident Evil (Boss Fights Books #25) by Philip J Reed. He tracked down and interviewed several cast members, and the book has some enlightening first-hand accounts of the game’s casting, filming, and recording. He even talks to the “RES-I-DENT EEEVILLLL” guy. If you know, you know.

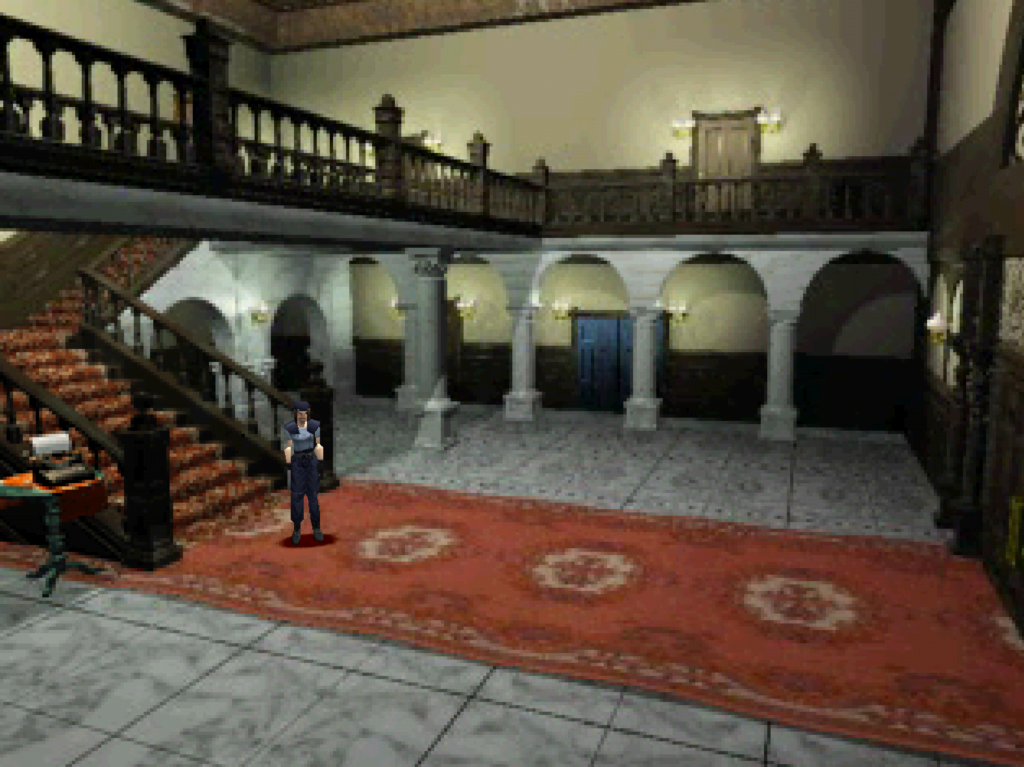

Anyway, what remains of Alpha Team is inside the mansion, safe from the hounds. The rest of the setup is slightly different depending on which character you picked at the start. If you choose Chris, he’s joined by Jill and Wesker in the lobby (Editor’s Note: Lobby? Is that what you call the big entry area of a mansion?); Barry is missing. If you picked Jill, she’s with Barry and Wesker in the lobby (Author’s Note: Yup! It’s lobby from now on!); Chris is missing. In both scenarios, the team splits up and ventures into the mansion to find their missing compatriot. Which admittedly doesn’t make a lot of sense, considering they most likely got locked outside with the dogs during preceding events… but denial is a hell of a thing, and they search the mansion for Chris/Barry rather than face the possibility that they left their friend to die just outside the giant double doors.

I chose to play as Jill for my playthrough, partially because I wanted to see Barry meme it up with his “Jill Sandwich” line a little later in the game, but mostly because I wanted eight inventory slots. Jill apparently has deeper pockets than Chris, who can only carry six items. Well, seven if you count his lighter. But then I’d suppose that means Jill can carry nine if you count her lock pick, and… okay… I’m getting lost in the weeds here. The point is Jill can carry more stuff. And she has a lock pick, which is waaay more useful than the lighter.

Now, the game’s manual may have something to say about it (I didn’t read it), but the game itself never does anything to suggest that your character choice at the start is going to be more than cosmetic. The truth is that who you pick is actually hugely important in both obvious and subtle ways. We’ve already talked about pocket space, and Jill is a clear winner there. But she can also take less damage than Chris and is slower. Chris has his lighter, which makes him better prepared for a few puzzles. Jill gets a lockpick that allows her to reach some parts of the mansion earlier than Chris and with less hassle. She can also get the shotgun without disarming the trap that protects it (it’s at this point that Barry rescues her and delivers his famous “Jill Sandwich” line). And speaking of weapons, Chris gets a flamethrower in his playthrough, while Jill gets a grenade launcher. Their stories also play out differently, with a different supporting cast and some different scenes and events throughout the game.

So yeah, I picked Jill. I’d be missing out on the flamethrower and meeting Rebecca Chambers (a surviving member of Bravo team). Still, I’d be doing less backtracking with all that extra inventory space, and I’d have a grenade launcher to help deal with those pesky Hunters in the second half of the game. There’s a distinct possibility that I’m missing some nuance diehard fans have discovered a long time ago that proves that Chris has less backtracking and is better equipped to deal with the Hunters, but *shrug* I’ve never been a min-maxer. I’ll pick Chris another time, and when I do, I’ll write up a supplement to this entry. I think that might be my approach to the games that have A/B scenarios—it’ll be interesting to revisit the games from a different perspective after I’ve spent some time with the later entries.

So Jill, Barry, and Wesker are in the mansion, and Chris is missing—probably locked outside getting devoured by dogs (Jill thinks so). They hear gunshots from deeper within the mansion (fine, maybe Chris got inside) and Corey Hart, I mean Wesker, the leader of S.T.A.R.S., sends Jill and Barry to investigate. We now have control of our character, and Resident Evil begins.

“But O.M.G.! What is wrong with this game’s controls? How can anybody play this? It’s impossible and stupid. We’re done. Retrospective over.”

Just kidding. Can you imagine? So yeah, Resident Evil‘s control scheme is infamous for being clunky and difficult. For those who don’t know, the control scheme for navigating the game’s environments was a bit different from what many gamers were used to. Pressing up on the d-pad made the character walk in the direction they were facing, while left and right would make them turn. But that sounds normal, right? It would be if the game’s camera followed you, but Resident Evil and many of its sequels used static camera angles that didn’t follow the character. You’re often watching Jill or Chris from a cinematic/dramatic perspective and no matter where they were on the screen, pushing up would make them walk in the direction they were facing. Western audiences called this type of scheme “Tank Controls,” but Alex Aniel’s book Itchy Tasty points out that the Japanese name for the control scheme is something closer to referencing a remote control car and I think that is a much better way to think about it. Still, I’m not here to try and change the accepted nomenclature. For the purposes of this series, I’ll call them tank controls.

Some diehard survival horror fans will (wrongly) tell you that the genre lives and dies with fixed camera angles and tank controls, going as far as claiming later entries like Resident Evil 7: Biohazard aren’t survival horror because of their first-person perspective and standard F.P.S. control scheme. I’m far from a genre purist and frankly feel that attempting to create rigid game genres stifles creativity. But while I don’t think tank controls are an essential part of the genre, I think they are irreplaceable in the Resident Evil games that have them (1, 2, 3, CV, REmake, and Zero). When Capcom remastered Resident Evil‘s GameCube remake for modern consoles in 2015, they added the option to use “normal” directional controls. You could finally push in a relative direction and Jill/Chris would run in that direction. It’s not just my nostalgia at work when I say that it’s an inferior way to play.

According to Itchy Tasty, Shinji Mikami and the rest of the developers behind Resident Evil had a “real-time” control scheme working for the original game but ultimately chose to use tank controls because they felt these created more fear and tension. The book also says that they kept the tank controls because real-time controls would have made dodging zombies too easy, but I’ve found the truth to be the opposite. For me, the tank controls avoid a layer of uncertainty that the updated analog scheme introduces when combined with the static camera angles. I think people wrongly assume the difficulty and clunkiness of the tank controls enhance the fear and tension in Resident Evil when in reality, it’s the weight and friction of the scheme that add to the experience. Tank controls anchor the characters to the world, making them a part of it, and the deliberate inputs of the player make the avatar an extension of themselves. Take tank controls away and suddenly, your character feels disconnected from you and the game they’re in. I don’t blame the people who hate tank controls. The learning curve can be steep and some people aren’t wired for it. It wasn’t until this most recent playthrough that I was willing to prop it up as the superior way to play; it took a lot of time with the control scheme to feel at home with it. But they make for a better game, even for a novice.

So we’re pressing up on the d-pad and walking through the mansion looking for Chris. Barry stays behind in the dining room to investigate a blood stain in front of the fireplace while we press on to see what we can find. We round a corner and interrupt a zombie wetly chewing on a dead member of Bravo team. His name was… searching… searching… doesn’t matter. The zombie turns around slowly and begins to shamble toward us. A first-time player is likely to raise their gun and start shooting, but we turn and run back to the dining room as the zombie slowly follows, letting Barry spend his cutscene bullets on the walking corpse. Had we stayed and fought, we would have discovered that it can take a considerable number of shots to drop a zombie and, checking our inventory, we don’t have many to spare.

Fans have done the math. They know how much ammo there is in the game and roughly how many enemies they can eliminate. The short of it is: there isn’t enough ammunition in the game to kill every enemy. Sometimes you need to run and sometimes you need to take damage, knowing you’ll be able to heal later. The hard part is learning when to fight, when to run, and when it’s okay to take a hit. So how do you learn? The first method is through failure. Early on, you’re likely to make poor choices with your resources and with this figure out that you need to take a different approach. The second method is through learning the layout of the mansion.

Resident Evil is, in many ways, an adventure game or even a Metroidvania. You spend a lot of time exploring, coming across a locked door, finding an item that unlocks that door, and then backtracking to find out what is behind it (usually a key for another locked door). As you progress, you learn which areas you’ll pass through most often and make combat choices to make your backtracking safer. If an enemy lurks in a room you think you’ll never need to return to and you have a reasonable chance of evading it, you take your chances. If there’s a zombie in a frequently traveled narrow hallway that will get you every time, you take it down. I recall a hallway I traveled often that had two lurking zombies. I never fired a single shot at them because I could confidently avoid them every time I passed through. But the key word here is “confidently.” Resident Evil has a trick to keep you from getting too confident. It’s save system.

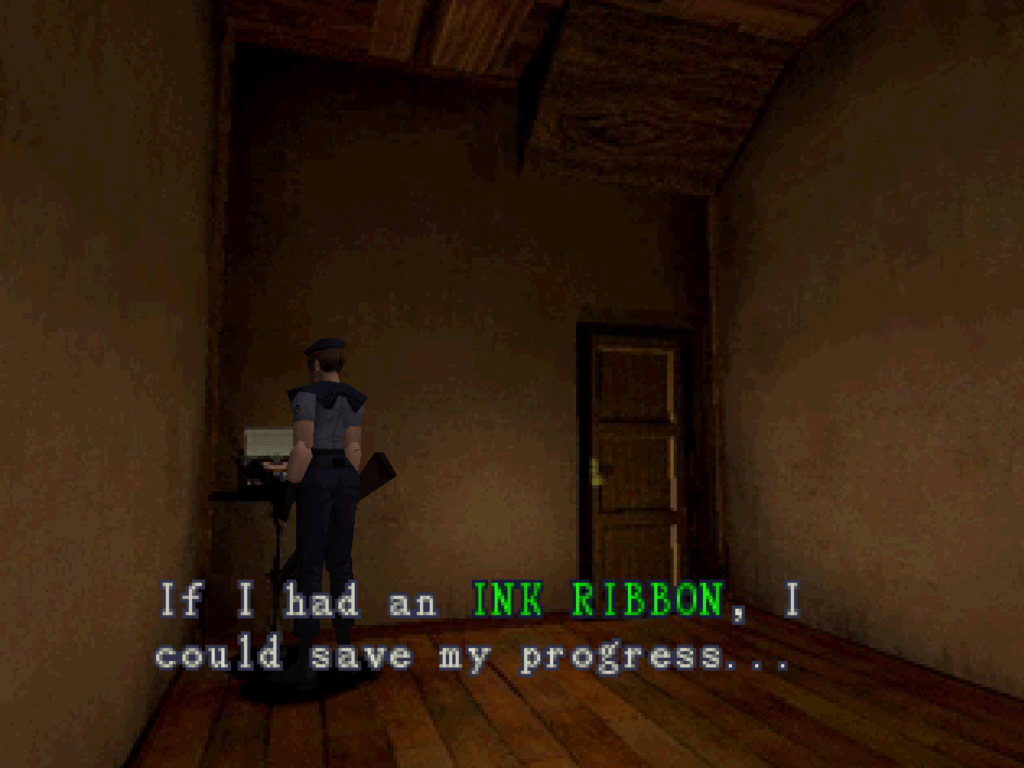

Let’s talk about ink ribbons. I mentioned in my REvisited introduction that I don’t like the ink ribbon save system. Many fans will say it’s a crucial part of the Resident Evil formula and lament that it was eventually abandoned in later entries. While I understand the spirit of the save system and what it was going for, I think ink ribbons ultimately add an unnecessary level of tedium to the games that take more away from the experience than they add.

For those that don’t know how the mechanic works, saves in Resident Evil are a finite consumable. You find ink ribbons throughout the game that can be used at various typewriter save points to save your game. Each ribbon you find gives you three saves, taking up a precious spot in your limited inventory. The idea is that it makes saving a deliberate choice and their finite nature adds tension to that choice. Do you burn a save after taking down a formidable enemy and finding a cool item, or do you try to make a little more progress first, risking needing to replay a longer stretch of the game to restore progress?

The system doesn’t work for two reasons. In most cases, the inventory pressure the ink ribbons create is easily mitigated by taking the extra time to store them in a save room’s item box, only taking them out to save and then putting them back after. Resident Evil‘s item boxes are spread throughout the game and are magically linked, so anything you store in one is accessible in another. There are a handful of cases where an item box isn’t near a typewriter, but they end up being the exception, not the norm. The other reason the save system doesn’t work is that the ink ribbons just aren’t scarce enough to make saving a concern. Ultimately, you end up with a save mechanic that makes the game tedious as you work around it. Plus, games have changed in the last 26 years. The system just ends up feeling inaccessible for people that don’t have a lot of time for video games. Lost progress in a game isn’t as acceptable in 2022 as in 1996. If Capcom ever releases a classic RE collection, I’d love to see them add some extra toggles that let players adjust how this system works.

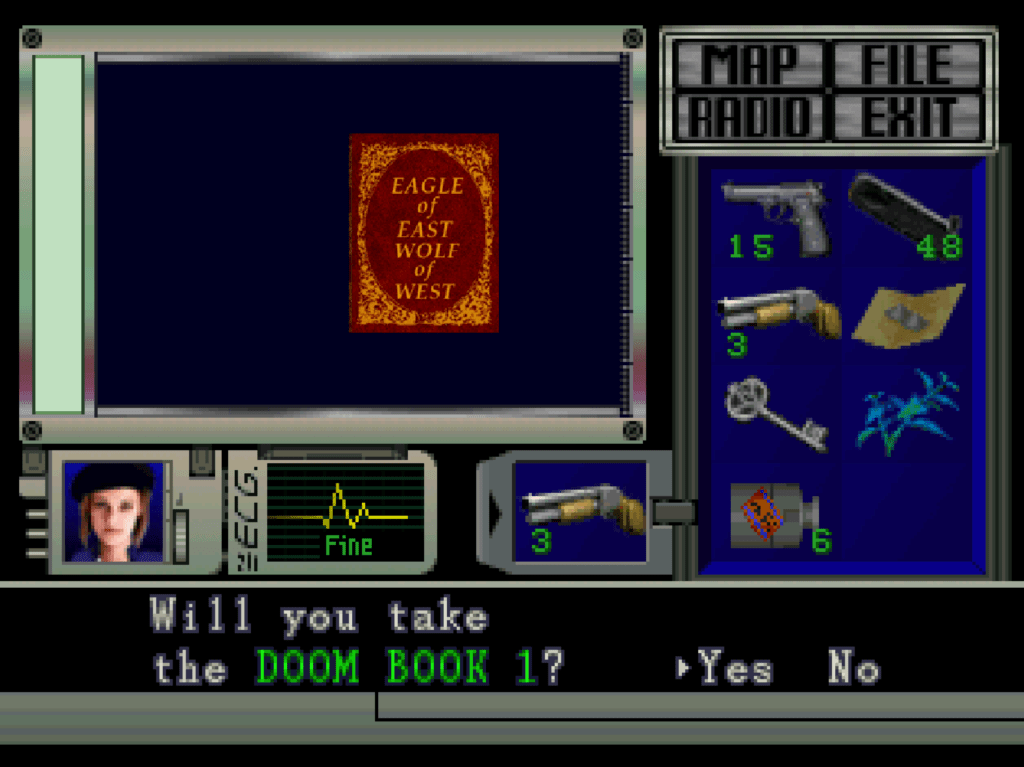

Alright. We were exploring the mansion and uncovering its secrets while juking and shooting zombies. In addition to Chris, Wesker is also missing. But as you roam the place, it’s easy to forget that you’re looking for them, instead letting curiosity draw you deeper and deeper into the massive, strange building. Doors are often unlocked with strange crests, jewels, and skeleton keys that are usually found after solving odd clockwork puzzles. The mansion is truly bizarre and I’d love a slice-of-life drama that shows its original inhabitants functioning within the space. “Dear, I’m off to read in the study. Do you remember where we put the Doom Book?”

In one room early on, we see a shotgun mounted on the wall. Upon taking it, we hear a loud clunk as some contraption triggers. We exit into a strangely empty room where the roof begins slowly lowering to the floor, threatening to crush us. If you’ve found the shotgun before finding a particular key, Barry will hear your cries for help, shoot the lockout, and pull you to safety. If you already have the particular key, Barry won’t be nearby to help you. You need to have found a broken shotgun to replace the working one, disarming the trap. In Chris’ playthrough, the broken shotgun is the only option with no Barry around to save him. Minor things like this can be a delight to discover during repeat playthroughs. Once while streaming the remake on Twitch a while back, I forgot the nuance of the shotgun trap and was crushed waiting for Barry to save me.

It’s too bad this is easily the most memorable puzzle/trap in the game (maybe the series?). Encountered so early, it sets a tone for how diabolical the mansion could be. It’s not just the zombies that are out to get you, but the mansion, too! I can see a case where the traps could get tiresome, especially given the game’s restrictive save system, but I’d have liked to have seen the game lean more into the house itself being a threat. And yes, there are other traps later in the game, like rolling boulders and gas chambers, but they fail to live up to the promise of the original shotgun trap. Side Note: I think the fact that the Resident Evil movies haven’t leaned more into the mansion is a huge missed opportunity, too.

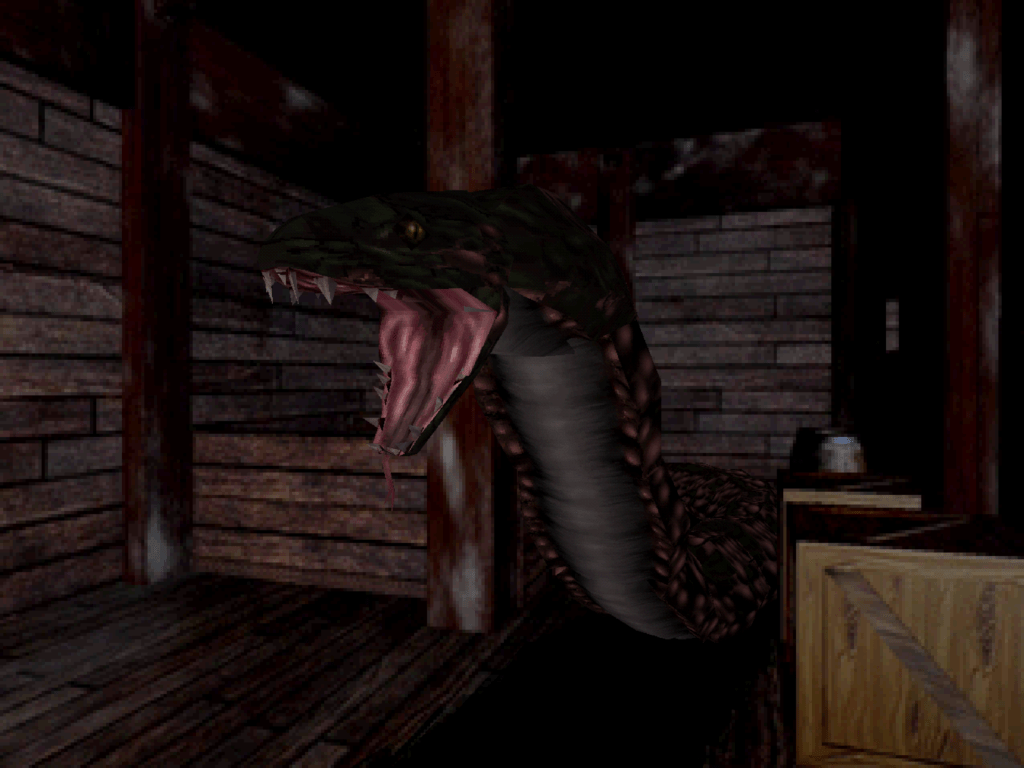

We eventually come across Bravo team’s Richard Aiken. He’s been badly injured and manages to force out a few words about a snake and antivenom. If you thoroughly checked one of the earlier save rooms, you might remember shelves that had various medicines. We run back to get the antivenom but return too late. Aiken dies. There’s one thing left to do: venture further down the hall and confront whatever killed him.

What we find is a GIANT snake. The thing is unnaturally huge, taking up most of the room, and is our first boss fight. I don’t know what the fan discourse is around the snake (beyond the fact that fans have named it Yawn based on its mouth animations), but I’m honestly not sure how I feel about it. Once, while telling Sean about Yawn, he asked, “is it a zombie snake?” To which I responded, “Probably? It’s not really clear.” See, the snake, beyond its massive size, looks like a pretty standard snake, and at this point in the game we’ve barely scratched the surface of the underlying plot involving Umbrella (a pharmaceutical company), viruses, and experimentation. By the time I’d seen the snake, I had already played enough other RE games to know what had created the zombies. I could conclude that some virus or experimentation was at work, but I’d be curious to know what first-time players back in 1996 thought. With no actual behind-the-scenes knowledge, Yawn feels like some kind of holdover from before they settled on zombies as their primary hook. It feels like it would be more at home in Alone in the Dark, a game that influenced Resident Evil‘s development.

As we get to later games in the series, we will encounter plenty of infected creatures, but they’ll usually be far more grotesque than what we get here, not just an oversized version of something we might see on a mountain hike. And Yawn isn’t the only instance of this. Later you come across some giant tarantulas that just look like, well, giant tarantulas. While they’re incongruous with where the series eventually goes with its monsters, it’s not surprising to find them here. The developers were almost assuredly figuring out the game’s identity as they went, hardly thinking about the capital “F” Franchise as they built the game. Also, who knows when the story came together during the game’s development? How far along were they when somebody wrote a single line about “Umbrella” or the “T-Virus?” Instead of being part of a cohesive vision, things like the snake and tarantulas feel like attractions in a haunted house you visit around Halloween. The thing is… I think I like that they’re there? They’re memorable. And frankly, I get a little tired of the more grotesque monster design we’ll come across later in the series.

Many people who haven’t played the original Resident Evil assume that the whole game takes place in its iconic mansion, but we eventually venture outside and begin to explore the rest of the estate. The outside paths are littered with snakes (regular-sized ones this time) and zombie dogs. By now, players should be comfortable with the tank controls and avoiding the snakes should be pretty trivial. The dogs, however, continue to be a serious threat.

We eventually come to the guardhouse, a building that is basically laid out like a small motel, complete with room numbers by the doors and matching numbered keys. Here, we come across the giant tarantulas and discover several other enemies waiting for us. Giant bees guard an important key and a tentacle reaches up through the floorboards and grabs us around the neck as we run through a hallway, chipping away at our precious hitpoints. Sharks (it’s not clear if they’re zombie sharks) chase us through waist-deep water in an odd facility beneath the building. It’s in the guardhouse that we really start to grasp that there’s more going on here than just zombies and a freakishly large snake.

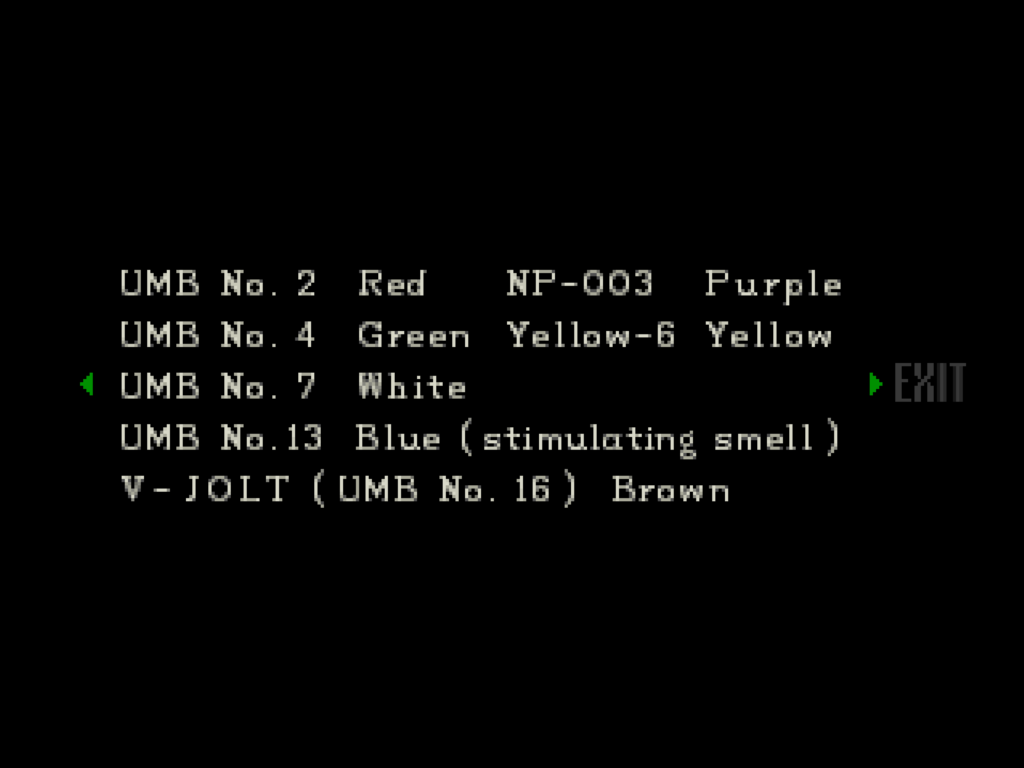

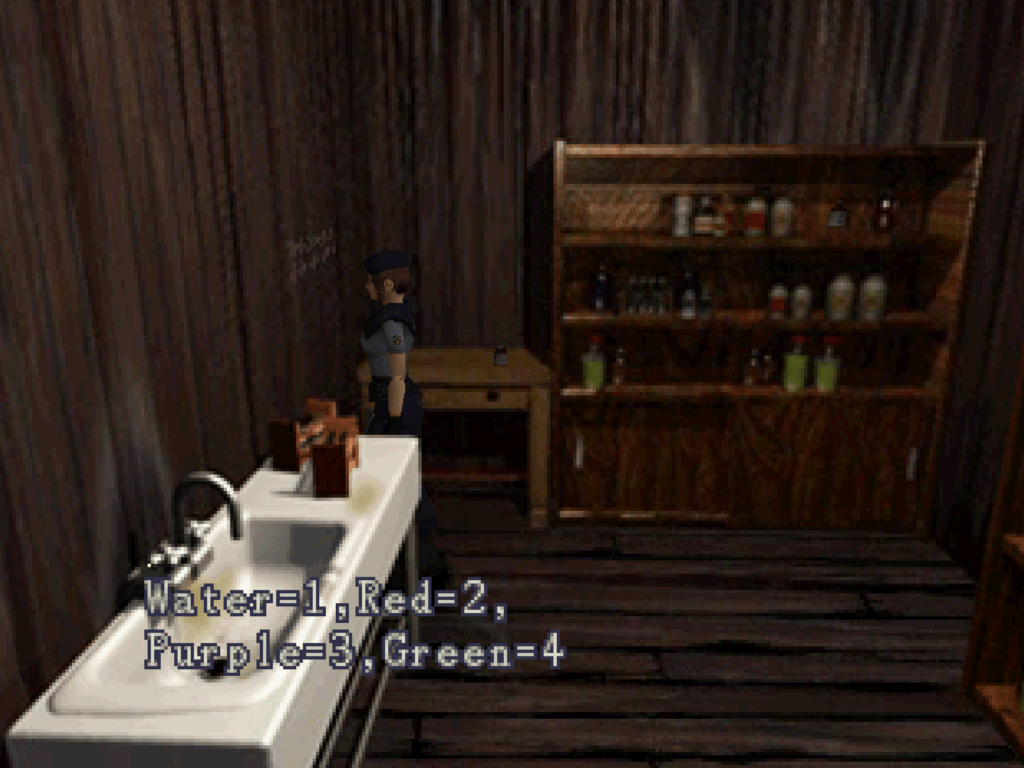

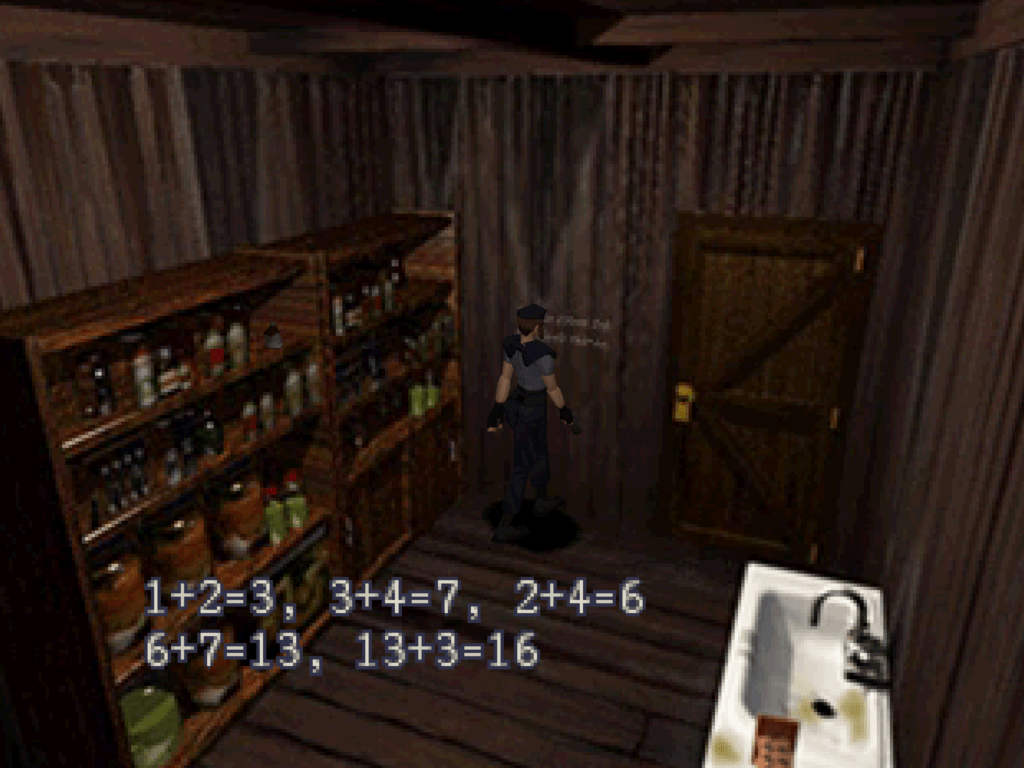

The guardhouse also contains the game’s most complex (optional) puzzle. Gathering instructions from various places around the area, we mix a chemical (V-JOLT) with a very particular formula.

Beneath the guardhouse, we find a mass of roots coming down through the ceiling, belonging to a giant carnivorous plant. Dousing the roots with the chemical severely weakens the plant and gives us the upper hand in the later boss fight, saving us precious ammo and healing items.

Defeating the plant gives us the remaining key item that allows us to finish exploring the mansion. It’s here that the game takes a fairly significant shift in its action, and I don’t feel like it’s a positive one. Upon returning to the mansion, we’re attacked by a new enemy that has crawled up from the depths of the lab: the Hunter. Hunters are bipedal lizard-like monsters with giant claws. They’re fast, deal a ton of damage, and have infested the halls, replacing most of the zombies and making previously safe passages dangerous again.

While I appreciate that this introduces variety to the areas that we’ve already spent hours backtracking through, the hunters are overused here. I don’t think fighting them is particularly fun, and encountering them so often throughout the halls ends up making our backtracking fairly tedious. Any fear introduced with their first appearance quickly dissipates as their encounters keep coming. It would have been much more effective if they’d used them sparingly and made them a significant threat by giving them more health and increasing their damage output.

Okay. Let’s talk about Umbrella. No, not the Rhianna song. I’m talking about the evil pharmaceutical corporation at the heart of the Resident Evil franchise and why we’ve encountered all these horrible creatures. In the context of the series, the most important parts of the story had already taken place before we ever pressed start. As things unfold throughout our playthrough, we discover through found documents that the mansion is more than an eccentrically designed house. Questionable experiments had taken place somewhere on the grounds and were responsible for the zombies roaming the halls. We learn about scientists being separated from their families, locked in rooms, and slowly dying. Slowly turning. The mansion, as it turns out, belongs to The Umbrella Corporation and hides a secret laboratory underground where they’ve been developing something called the T-Virus, a virus that turns people into zombies.

You may ask, “Why would Umbrella want to make a virus that turns people into zombies?” It is a VERY fair question (and one that the Paul WS Anderson Resident Evil movie series severely fumbles, but that’s for another time). They developed the virus for military use. Umbrella wanted to create bio-organic weapons that were more effective than ordinary human soldiers and more resilient. In 1996, the virus escaped containment in the lab beneath the mansion, infecting the researchers and eventually spreading to the mansion itself.

After we deal with the Hunters and have a very strange encounter with Barry, we get the last items we need (including a magnum) to finally descend into the lab, where this whole mess started. We find that Wesker has already made his way into the laboratory and learn that he has been working for Umbrella the entire time. He’s blackmailing Barry into helping him by threatening his family and has imprisoned Chris (or Jill in Chris’ campaign) somewhere else in the lab. After he reveals his betrayal, Wesker unleashes the Tyrant, a monstrous super soldier born from Umbrella’s T-Virus research. Before attacking the player, the Tyrant turns on Wesker and kills him with its massive claws. We raise our magnum, and using its VERY precious powerful ammo, drop it in just a few shots.

It’s here that playthroughs can really start to diverge, leading to multiple endings. Depending on various factors, the characters and the mansion’s fate can be different. In my playthrough, Barry died and Chris and Jill escaped the mansion in a helicopter with Brad Vickers. Canonically, Chris, Jill, Barry, and Bravo’s Rebecca Chambers (who?) all escape with Brad as the mansion explodes behind them. The funny thing is, it’s impossible to get the canonical ending in-game, as it mishmashes Chris and Jill’s campaigns and conclusions together.

But that’s it! They fly off into the sunrise (I think it’s morning) and leave the nightmare behind them, ending Resident Evil.

When I was considering starting this project, I was worried that returning to the original PS1 games would be a chore. It turns out, at least with Resident Evil 1, I had nothing to worry about. I enjoyed revisiting this classic and enjoyed it a great deal more than I did 18 years ago. Sure, it’s clunky and tedious at times, but there is some true unironic charm to be found here. Also, as the series has become more important to me over the years, it’s cool to go back and re-experience where it all started. And that’s what this series is all about! I can honestly say that it won’t be another 18 years before I replay this game again.

Thanks for joining me on this first entry. There is, of course, so much more that I could say about this game, but I’ll never finish this project if I try and say everything. Sean and I are already making plans to record a podcast episode about the game and I’m sure it will end up being a great companion piece.

With that, I’m moving on to Resident Evil 2 as I continue my retrospective. See you next time!