After Paizo took over the publication of Dragon, Dungeon, and Polyhedron magazines from Wizards of the Coast, all three periodicals went through substantial changes. Soon, Polyhedron would be gone for good, but oddly this wasn’t the change that had the biggest effect, not just on D&D but the entire RPG medium. Instead, the real game changer (pun extremely intended) was to be the decision from Dungeon‘s editors to begin releasing large-scale, serialized modules, which, following somewhat in the format of the Sunless Citadel series from third edition, were dubbed an adventure path. Paizo was only able to publish three of these before Wizards snatched its rights back for the magazines in preparation for the game’s fourth edition, but this early model allowed Paizo to experiment with the format before branching out on its own. Its eventual heir to D&D 3.5, Pathfinder, is known for a lot of things, but chief among them is its long-running series of adventure paths, dozens of lengthy serialized modules whose massive amount of support radically altered expectations within the hobby.

Because these adventure paths were serialized, I debated how to cover the planar adventures from these series. Both the first and third of these paths contain relevant material, setting lengthy chapters within the planes, and they’re also somewhat interlinked with what else Paizo was putting out in Dragon and even its book-length collaborations with Wizards (i.e. Fiendish Code I: Hordes of the Abyss and Expedition to the Ruins of Greyhawk). That being said, while the adventures can be run as on-shots, that’s neither the best way to use them, nor what they’re intended for. Really, each of these is just a chapter in a longer story, so I decided to cover the paths as a whole, as otherwise this column would become even messier than it already is.

This approach works particularly well with The Shackled City, Paizo’s first and perhaps least-successful adventure path, as unlike its successors the entire series was later released as a single, hardbound book by the same name. Despite fan support and interest on Paizo’s part, this would never come to pass for the Age of Worms or Savage Tide adventure paths that followed it in the pages of Dungeon, as this conflicted with Wizards’ transition away from 3.5. This is particularly unfortunate because The Shackled City‘s physical book is a magnificent piece of work. While the campaign itself has many issues that make me hesitate from recommending its use today, Paizo went all-out with the book’s production, including an entirely new chapter of adventure not drawn from Dungeon, plus expanded material splattered throughout pulled from web content. In addition, the book is in full color, includes dozens of pages of maps and handouts, and is elegantly laid out. At $60 MSRP this was a deluxe edition by default, but at least that money felt well spent, and it’s a pity that this was never matched with similar hardbacks for these other adventure paths.

So what exactly is The Shackled City about? Well, uhh, hmm… that’s actually one of the problems with the adventure as a whole. While the entire module is focused on the city of Cauldron and its big overriding story concerns a half-baked scheme to drag this volcano-set location into Carceri, most of the individual chapters barely concern this overarching plot. The whole dragging-part-of-the-Prime-into-Carceri storyline only becomes particularly relevant halfway through the adventure, and is resolved several chapters before the campaign’s conclusion. It’s just not a cohesive work, which is somewhat to be expected considering that it had half-a-dozen different authors (Jesse Decker, James Jacobs, Tito Leati, David Noonan, Christopher Perkins, and Chris Thomasson all contributed at least one chapter, plus shifting responsibilities regarding its plotting and overall editing bouncing between Thomasson, Perkins, and Jacobs), but is still disappointing, especially in light of Paizo’s later works. Eventually, Paizo would become truly excellent at patching these massive stories together, and the excellence of their adventure paths is the company’s calling card. Still, D&D has a long history of somewhat ill-fitting adventure paths (think of Gary Gygax’s Hommlet series from the 70s-80s). The work’s goal of each chapter standing on its own, which was achieved to greater-or-lesser extent throughout, made cohesiveness particularly difficult to achieve, as did its publication in Dungeon, which especially in its later years was expected to include a gauntlet for players to fight through with almost every adventure it published. The Shackled City isn’t great as a whole, but it does feature dungeons, investigations, and even interplanar journeys. While it contains an absolute ton of fighting (far too much…), it also requires quite a bit of roleplaying and features numerous memorable characters. If you’re looking for a single, compelling story for players to take part in on their journey from levels 1-20+, then you should probably look elsewhere, but if you’re hoping for wave after wave of fun sessions that never quite make sense when you think about how they fit together—which, let’s be honest, is how most campaigns really function—then this is still a worthwhile book.

But back to the main topic, The Shackled City is ultimately about the city of Cauldron itself. This is a city-based campaign, and most adventures involve delving into warrens beneath it or visiting nearby towns and dungeons with links back to Cauldron. The city is the most prominent NPC in the adventure, and rescuing it from demise is ultimately the goal, even though players probably won’t know this for a very long time… and weirdly, the parts of the book we’re concerned with right now are also the few parts that largely do away with Cauldron entirely.

Of the book’s 12 adventure-chapters, only three leave the Prime Material Plane. The first of these is “The Demonskar Legacy” by Tito Leati, which takes players to somewhere never before seen in an adventure: the Plane of Mirrors. Or at least one of the planes of mirrors, as these are all demiplane-esque realms connecting a handful of mirrors together, though not the entirety of mirrors everywhere. First mentioned in the Manual of the Planes, it reappeared in the Fiend Folio entry for a race called the nerra, who live in this somewhat non-canonical plane. The Shackled City treats the nerra and their plane of origin as a known part of the multiverse, (there’s not any explanation of who they are in the book, so if you don’t have the Fiend Folio handy, or even if you do but don’t remember them, you’re probably confused when reading this section of the adventure), and nonchalantly drops them into the end of this chapter.

In order to access this plane, players use an artifact called the Starry Mirror that “was originally linked to four other portals at distant points across the Material Plane, of which only one other remains functional today.” Players who jump into this mirror need to deal with a rather opaque and quite obnoxious puzzle involving an extradimensional space that endlessly duplicates and requires the use of a dumb code possibly found earlier in the adventure. As such, this version of the Plane of Mirrors is actually pretty disappointing, and it’s unclear how exactly it links between the Starry Mirror and the normal version of the Plane, but oh well. It’s still an interesting development, as at this point all of the planes from outside the core cosmology that happened to be detailed by the Manual of the Planes seem to be part of the game’s multiverse after all. Which doesn’t make much sense, but whatever—unlike many cosmological changes, the addition of odd planes like these is only a good thing.

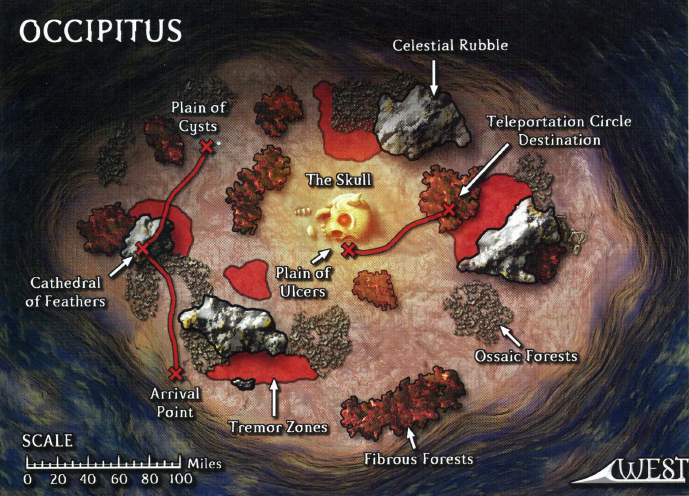

Following this adventure-chapter, players find themselves—for convoluted and largely nonsensical reasons—in a never-before-mentioned layer of the Abyss called Occipitus (in a chapter titled “The Test of the Smoking Eye” by David Noonan). There, they eventually succeed at a quest to become the layer’s ruler, which is hard to describe as anything but disappointing, as it turns what should be the most epic of epic quests into a humdrum bit of mediocre puzzle solving. However, part of why this particular part of the Abyss is unpopular, and thus easy to rule over, is because of its tainted backstory:

Even to demons, Occipitus is a cursed place. The 507th layer of the Abyss was once Admiarchus’s realm, but since his imprisonment 50 years ago it has lain dormant. Fiends who tarried there seemed to suffer all manner of misfortune, from madness to magical maladies to overly ambitious subordinates. To most demons, the cause seemed obvious—the chunk of Celestia that Occipitus absorbed long ago was somehow still influencing events there.

It’s most likely that PCs in this adventure never learn the full backstory of Occipitus and its ruler, Adimarchus, but if they do manage this feat they’ll find out that Adimarchus is a fallen angel, and in order to quell his rebellion a part of Celestia was lopped off and deposited straight into the Abyss. It’s a rather neat bit of cosmological history that seems right out of the Planescape universe. Parts of planes being shunted around due to the actions of their inhabitants is a frequent concern there, and the backstory for the realm is by far its most interesting aspect.

Adimarchus was deposed due to plotting from Graz’zt and his son, though their machinations are barely relevant for The Shackled City. This left Occipitus without its ruler, raising the question as to how does a person become the ruler of a layer of the Abyss, anyhow? In this particular case, it turns out to be rather easy. PCs need to go through a few basic trials, none of which are terribly interesting or creative. As with nearly every other time the game has headed to the Abyss, what’s supposed to be a universe composed of limitless chaotic evil is, in practice, disappointing and small. “Occipitus appears as a great basin surrounded by impossibly steep mountains that raise to the sky.” So in essence, it feels like an old video game with obvious invisible borders, to the point that it’s much smaller than the areas players recently explored on the Prime. Many demiplanes seem larger than the area of Occipitus that PCs get to play in, and the whole quest feels oddly stapled onto the adventure, though I should note that this wasn’t the part added just for the book, it just feels that way. Learning about a new demon lord and his layer ought to be thrilling, especially when they have some weird quirks and a unique history, but unfortunately this sidequest to Occipitus is one of the most lackluster parts of the entire module.

Oddly, Carceri, a Hell plane in its own right but one that tends to play second fiddle to the Abyss, Baator, and even Hades, turns out to be a lot more dangerous and terrifying than its neighbor, even in just its topmost layer. While this makes sense from the adventure’s structural point of view—players will visit here when at level 20 or so as the culmination of this entire campaign—cosmologically this seems kinda nonsensical.

The chapter on Orthrys, “Asylum” by Christopher Perkins, includes a return of the Bastion of Lost Hope (I believe it’s always mentioned when Carceri comes up because there are so few known locations on the plane, but I still find this funny because it’s primarily just the base for Anarchists), but also a few new locations as well. Harrowfell is a huge tower being held by demons, though it’s quite dull and barely described. More relevant is the prison tower Skullrot. Here, Adimarchus is the central inmate, but alongside him are countless other prisoners. It’s a noteworthy location because it fleshes out one of the more pertinent parts of this plane, which is to say its prisons—though this isn’t the first Carcerian prison to show up in D&D, when that’s the primary theme for a plane you can never really have too many of them. Skullrot isn’t just an ordinary prison, either, it’s “a prison for beings deemed too dangerous to roam free and too valuable to kill,” i.e. Adimarchus. Since the players should at this point be level 20, this all makes perfect sense.

However, the logic of how people end up in this prison and who appoints its wardens is weirdly unclear. It’s run by Dark Myrakul and a few of his henchdemons, and the whole location seems like an outpost for Graz’zt, but if that’s the case then why isn’t it just on his layers of the Abyss? And Carceri as a whole is only sketchily detailed, the assumption being that characters this high-powered won’t have much trouble finding whatever it is they’re searching for post-haste, but even so what’s included is extremely lacking. Essentially, this is exactly the type of planar excursion that Planescape was fighting against, consisting of a gauntlet of battles in an otherwise lifeless and monotonous location. The most interesting thing to see here is an inexplicably deformed advanced kelubar demodand (gehreleth) with six arms and a penchant for singing, but even with him it’s most likely players never so much as strike up a conversation.

Ultimately, the planar material for The Shackled City disappoints. Which isn’t a huge surprise since the whole adventure hasn’t aged all that well, partially because of its relentless need to turn every location into a gauntlet and partially because Paizo hadn’t figured out how to seamlessly patch these things together yet. Only one of its 12 chapters doesn’t include at least one dungeon for players to fight through, and as a result the focus of what’s here, planar and otherwise, is never tone, theme, or ideas. These other planes are simply exotic arenas to fight through, whereas in the best planar works they’re strange ecosystems like any other. I appreciate what The Shackled City did and consider it a monumental achievement, but it’s ultimately a very railroad-y, fight-heavy adventure path that for the most part used other planes of existence in uninteresting ways.