As of 2005, Wizards of the Coast still didn’t seem to know what to do with the Far Realm. More than anywhere else, it both was and wasn’t part of the game’s core cosmology, dating all the way back to 1996 but still rarely explored. You get the sense that the designers liked it, players liked it, but moving it to an official location would require revising the Manual of the Planes. Instead, it continued pushing its way slowly into the game, and the simultaneous publication in April 2005 of the Lord of Madness splatbook focused on aberrations and the feature article “Enter the Far Realm” in Dragon Magazine‘s (#330) would seem like the point of no return… though it still wasn’t. Both works manage to consider this plane—if it even is a plane and not something weirder—only borderline canonical, but at the same time they fill in some of the missing information about what’s going on with the location. At this point, the game is trying to have it both ways, and the result is a bit awkward.

Let’s start with the Dragon article, as it’s the more directly relevant part of this pair. Written by the Far Plane’s original designer himself, Bruce R. Cordell, this is a solid 17 pages of content focused on details about this unusual location in the game’s cosmology… though all without ever really stepping foot in the plane itself. Which makes sense given the insanity of this plane and is a good conceit for most campaigns, though it’s not quite what would be hoped for from most interplanar travelers. This isn’t a complaint, though, as visiting any Lovecraftian nightmare plane should be instant death, or worse, if it’s all it’s cracked up to be. As such, instead of venturing into the mind-crushing pseudo-plane itself, Cordell explains what happens when a rift from the Far Plane enters the Prime and the myriad effects this can have there.

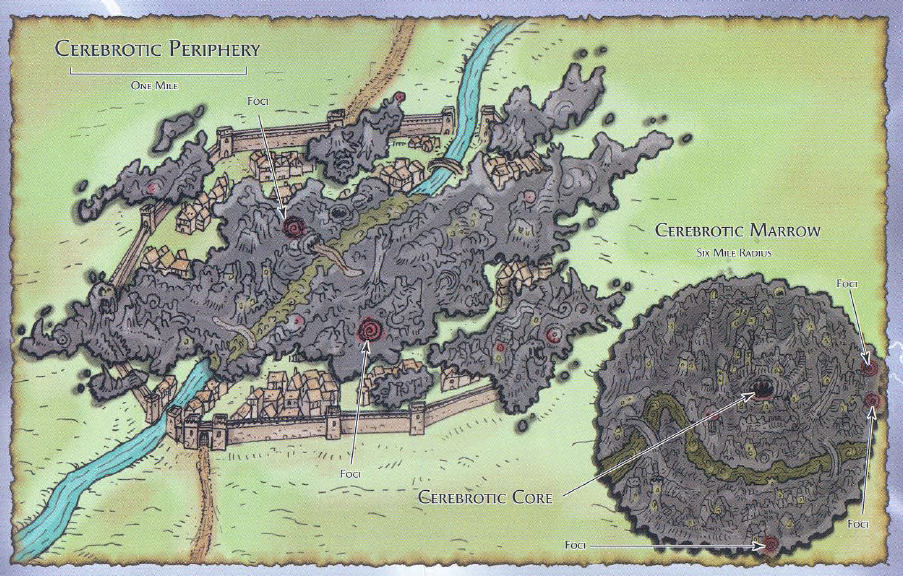

Probably because Cordell was the designer of The Gates of Firestorm Peak, the backstory as to how this plane was discovered largely repeats what was contained there. Once this is out of the way, rather than reiterating more of that work, he dives into a more generic version of what a Far Plane incursion can be. This is described as a cerebrotic blot, a location centered around a small hole between this reality and the Far Plane. Information is included about what the environmental effects of a blot are, what mutations this leads to in nearby creatures, and even how they change over time.

The second half of the article is devoted primarily to how players can interact with these blots, which for the most part comes in the form of cerebrosis, a word he coins to mean studying the Far Plane. Characters can receive a feat related to this, and from the feat learn new spells, which on the whole are slightly weaker than other ones of their typical levels unless powered up, at which point they’re stronger but come with dangerous risks. New monsters and magic items round out the rest of the article. I may sound a bit dismissive, but really there’s a lot of great material here, and the details about spells like Dimension Rift are where we learn more about what’s actually happening on the Far Plane itself. Why teleport the old-fashioned way when you can travel through a disgusting tube filled with “awful creatures” who will claw at you during your entire journey, possibly devouring you whole and leaving your corpse hundreds of years in the past?

I’m always a fan of a narrative being told through details (yeah, I’ve been playing Soulsborne games since they first arrived on American shores, I’m one of those), and Cordell’s article is a great example of this. While it’s easy to disregard the entire Far Realm as a Lovecraft rip-off, the more you learn about this location the more it’s clear that this isn’t quite what’s going on here. Even most of the art and maps for the piece—that’s right, somehow there’s maps here, though who drew them isn’t credited unless they’re also by David Birchan, which seems both unlikely and unclear—are excellent. It’s not quite a primer on the Far Plane itself, which is going to have to wait until a far worse cosmology takes over the game, but still makes for intriguing material and is something I’d happily bring into a campaign.

Because this article was meant, at least tangentially, to tie-in with Lords of Madness, I’d assumed that the book would have a lot more to say about the Far Realm—after all, it’s all about aberrations, and what’s more aberrant than a plane outside the multiverse’s cosmology? Unfortunately, this turned out to not be the case, and even the new tsochar monsters developed just for this book don’t have Far Plane origins. Which honestly seems kind of off, especially given that some of these aberrations worship a Far Plane entity. Instead, the Far Realm is mentioned as simply an option for DMs who want to change things up for their particular campaign. Every monster actually discussed in the book, however, has a canonical origin that’s either unknown or simply the result of magic gone awry. This is also how aberrations were thought to have originated in earlier editions, but given how much retconning is going on with the rest of third edition, I figured this would be the time to throw the Far Realm into the mix more fully. Unfortunately, we’ll have to wait a bit longer for that, though there’s still a smattering of worthwhile planar information hidden within the text.

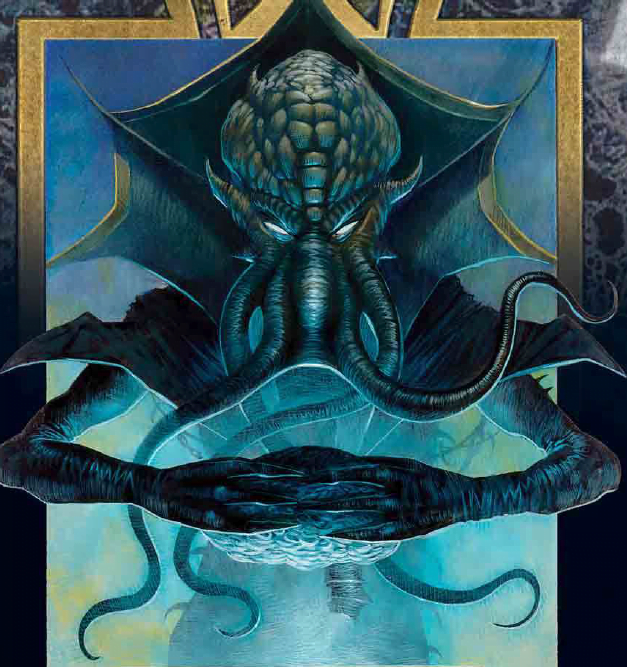

For instance, the Elder Evils worshiped by aboleths “existed before the deities of the current world, and they know that the Elder Evils will remain after the world has come to an end. They are beyond eternity.” These Elder Evils first appear here, with a description of five the aboleths like best, though there’s also a subsequent section noting how these are all pretty much Lovecraft rip-offs (“perhaps they are just alternate names”) and how to best include those deities instead. Oddly, these are not the same being as the “Unhuman Gods” listed later in the book, but rather a unique set of weirdo creatures from beyond the multiverse, which somehow go unmentioned in the rest of the book. If you can’t tell, this part doesn’t fit well, and I don’t believe it ends up being continued in any form by other authors, even in the book of the same name—guess we’ll see if my memory is correct about this in the near future.

The Beholder section of Lords highlights my primary issue with the work as a whole. In second edition, Beholders were one of three monsters given numerous entire books themed after them, the other of these monsters included here being mind flayers. But in third edition, instead of a book, they’re given just 24 pages of material. Which is a lot, don’t get me wrong, but still much less than they received in I, Tyrant, plus the many details learned about them in adventure modules and stories elsewhere. The end result is a simplification and reduction. As such, their deities are reduced to solely the Great Mother, leaving Gzemnid completely forgotten, let alone more obscure individuals like Kzamnal (not a full deity, but still a culture hero of sorts). Likewise, the one planar addition here is that of a beholder city on Gehenna, which makes no sense given both the alignment of the plane and the Abyss’s relationship with the Great Mother. I get the sense that the writers of this book were told to maybe skim earlier works, but not to stress much about making everything match up with what came before, which can’t help but only frustrate obsessive, longtime players like myself.

It was impossible to escape the feeling that the book’s authors never took a look at Planescape, which meant that Maanzecorian and Gzemnid were left out entirely, even though I found these secondary gods to be some of the more interesting aspects of these races. Material from the Illithiad and its linked adventures is mentioned, but Maanzecorian’s death doesn’t even warrant a footnote, even though he still crops up in another third edition work from just a couple years prior, Gwendolyn Kestrel’s web enhancement for Underdark.

The result of this erasure is that instead of seeming like the all-encompassing companion to more encyclopedic works like The Draconomicon, Lords of Madness‘ write-ups felt like shortened, crib notes version of these many weird creatures. Not only had several of them received more detail before, but what was here simplified the aberrations it covered and with this flattened them and made them less interesting. The best parts of the book are the chapters on creatures like aboleths and grell whose backgrounds were sketchier until now, but when it came to the mind flayers, beholders, and neogi, who’ve had a lot written about them in the past, I was far more disappointed.

Oh, and while speaking (very briefly) of the grell, they apparently originated in a distant Prime plane filled with weirdness before traveling by way of the Plane of Shadows to more normal parts of the Prime. Which is a great planar origin—I always love exploring how weird the Prime Material Plane can be—but unfortunately not one that lasted. Apparently they were later retconned just a few later into being from the Far Realm after all, which just drives me crazy. Come on, Wizards, don’t you even read your own works anymore? If I can do this paltry research for a free column on the world’s most obscure game website, you can do better for officially published books.

As much as I’m tempted to prattle on even more about how bad a job this book does with the game’s continuity—I get it, ok, they don’t care at all about the game’s canon, even though it’s not that complicated and it’s grating to old fans when they continually screw it up and retcon things over and over again—I actually liked this book for what it was, and even liked a few planar bits that managed to sneak into the work. In particular, I was fond of Mak Thuum Ngatha, who is described as “an entity from the Far Realm.” Other deities would have this trait retconned into their past, but as far as I’m aware this being was always from there, and is suitably a weirdo worshiped only by weirdo races. I also appreciate that The Patient One isn’t yet conflated with Tharizdun, though it seems possible the later’s mention here is one of the first seeds of his return to wild prominence in the game’s meta-story.

So yeah, it’s a book that does a bad job with the game’s continuity. Some of its ideas are still inspired, such as its invention of the Ebon Mirror and Codex Anathema, but as with other third edition books it feels a bit afraid of saying anything definite in fear of ruining someone’s homebrew campaign. Often, tie-in Dragon articles seem like they really should’ve been part of the original work, but in this case I’m quite happy that it wasn’t. Cordell’s essay is a wonderful combination of lore and crunch that continues growing the multiverse in an interesting new direction, while Lords of Madness for the most part erases both lore and parts of the game’s cosmology. This is a book I was quite excited to delve into, as these monster-focused compendiums were one of the best parts of D&D‘s third edition, but despite excellent writing and art, it was the ideas themselves that left me disappointed here, leaving me to reluctantly suggest giving the work a skip.