While The Planescape Campaign Setting does a more-than-adequate job of describing the somewhat strange, arguably new world of the other planes of existence, one thing it doesn’t do is tell anyone much about how to actually run an adventure there. Oh it tries a bit, and features some broad advice about tone and theme, but it can be hard to imagine how this looks in actual practice. Be big and be worldly, and, well, create adventures, I guess. Likewise, its booklet “Sigil and Beyond” also features two “quick-start” campaign ideas, which combined are given three pages of information and little other direction than to get the party of adventurers to Sigil and then possibly start some light intrigue with the factions. Neither of the prompts are particularly inspired, and they give little sense of why a DM would want to run these ideas rather than more traditional fantasy storylines. As a result, the Setting leaves a big question sitting at the end of it: what next?

Fortunately for players, TSR’s support for Planescape was, at least for the first couple years, both frequent and timely (seriously, its schedule for these often-huge supplements is, in retrospect, more than a bit nuts). Only a month later, The Eternal Boundary was released, which is a worthwhile read for any fans of the setting regardless of whether you’d ever want to run it. This is something I will say about all of the better Planescape modules, and seems a point worth making since in general adventures are the most neglected type of roleplaying game supplement. Most dungeon masters, at least that I’ve known, prefer to create their own material, for reasons of both creativity and flexibility. However, that doesn’t mean that having an example to work from is a bad thing, and this is especially true for odder settings. It’s one thing to read about how the factions work and what they believe, but it’s another thing entirely to read about them in action, and this, I think, was the most important legacy for The Eternal Boundary.

Which isn’t to say it does a bad job of reemphasizing the Setting‘s tone and theme, especially when considering that Boundary is only 32 pages long, unless you include the lovely maps and illustrations on its accompanying DM screen. That’s fine, though, as this module wasn’t meant as an adventure path, it seemed meant more as a template for adventures in Sigil, illustrating what a low-level Planescape story looks like and how to run the factions. It’s not here as a showstopper to blow characters away, but I have a weird appreciation for this, especially after recently reading Throne of Bloodstone. Like most longtime tabletop RPG players, I’ve been in plenty of campaigns about saving the world from the big bad, whereas a good mystery procedural can be oddly hard to come by.

Boundary is divided into three parts plus an introduction, though it’s the first part and introduction that are most important. The introduction matters so much both because it gives the context that makes the rest of the story make sense, and because it sets down the guidelines for things a DM should know before any adventure that contains Sigil: namely, how are the factions involved. When I first read about Planescape they were so overwhelming that I wanted to ignore them in favor of wandering amongst the planes. Remembering the differences between 15 distinct groups (and we haven’t even gotten to the sects yet…) and considering how they interact with each other in every circumstance that touches Sigil is a bit much. At the same time, though, they’re what makes Sigil so different from other cities, and more interesting than just throwing a bunch of planar gateways into Waterdeep. What Boundary does so well is illustrate that DMs don’t need to know how every single faction is involved with a story, just the ones relevant to it, and the ones the party is involved with. That this adventure can easily work as the start of a campaign, given its focus on low-level characters, makes this even easier to understand, even if it may take a few sessions for anyone, including the DM, can keep clear in their mind the differences between the Doomguard and the Bleak Cabal.

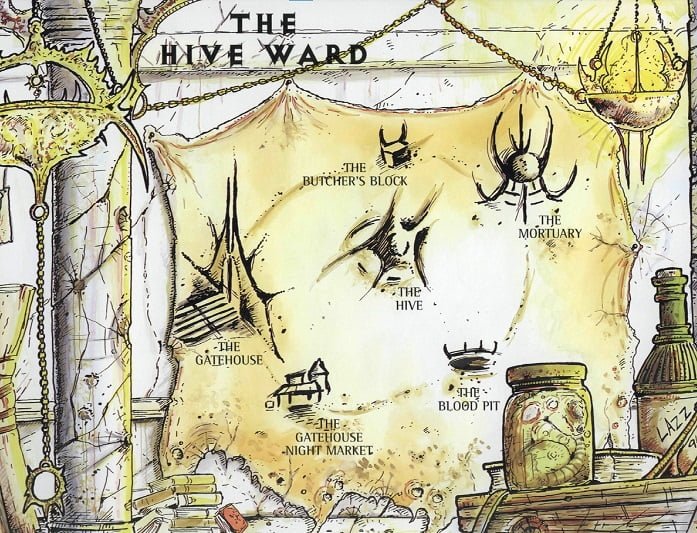

In a way, it’s this first part that is the whole adventure. Players are told to look for a missing person, told he’s in the Hive, then given a list (or map that functions largely the same but with some nice design flourishes) and told to go nuts with it. The openness here is wonderful, and at the same time it leads to this adventure feeling a bit like a guide to the Hive in miniature. No, we don’t get particularly long explanations of many of the key locations, but we do get enough that characters can visit the area and, assuming our imaginations aren’t completely fallow, fill in the blanks ourselves.

As I said earlier, a good investigation, at least in my reading and playing experience, isn’t particularly common for D&D. This is particularly true for the game’s older editions, which really didn’t know how to handle this type of roleplaying very well as they’re focused so much on combat mechanics. This is unfortunate, as a good mystery is more enjoyable to deduce than saving the world from some unclear evil force. It forces a level of roleplaying that saying “I attack it with my sword” over and over again doesn’t, with players thinking about the world and how they fit in it in order to solve a puzzle. It’s a much better introduction to a space like Sigil than a dungeon run would be, making for an excellent introduction to the setting. That being said….

The other thing that’s difficult about an investigation format is that it requires players to motivate themselves quite a bit, to follow the clues and come to the right conclusions. Here is where Eternal Boundary doesn’t do quite so well. Admittedly it can be difficult to spot these things at times, but as I’m currently running a version of this module, believe me when I say that the reasoning for following up on these threads and taking them into the second and third chapters of the scenario are tenuous at best.

Part two takes players into the Dustmen’s mortuary, which is an interesting idea and fleshes out what this building contains, but why and how players might want to do this isn’t well explained. There’s a listing that says they can kinda choose to do what they want, but that requires quite a bit of desire, and at least for my players they were more interested in the MacGuffin of treasures than they were about the mystery of the dead bodies. The way around this problem seems to be either railroading them or at least heavily hinting that this is where they should go. This is the book’s weak link for me, making it an interesting resource (to the point that its version of the Mortuary would be largely reproduced by Planescape: Torment), but not quite as strong when it comes to running an adventure.

The module’s final chapter takes players to the plane of fire, which is better in almost every regard. If players make it this far, they’re certainly motivated to figure out the end of the plot and take things to a resolution. Again, this section is open as far as allowing players to figure out the best approach to the problem. It’s a simpler problem, in that it’s pretty much “beat up the bad guys,” but even so it feels more fitting to me for the setting than sending players off into a dungeon. It also does a great job of emphasizing the idea that Planescape adventures may begin in Sigil, but they can head just about anywhere. The plane of fire isn’t the most interesting place in the multiverse, but we’re both shown how to make it playable (which is actually pretty important considering the setting’s tacit goal of allowing low-level characters to visit the inner planes) and that this is both a typical and extraordinary conclusion to adventures at the same time. These sorts of things simply happen in the Planes, and if players are already experiencing this at level two or so, then they should prepare for even more exciting locations in the future.

So despite its flaws, The Eternal Boundary seems worth running to me, and more than that it’s worth reading for anyone interested in the planes. It’s not a mind-blowing, earth-shattering module, but then it’s not supposed to be. Aside from the tenuous links in its second chapter, it succeeds at its goal of introducing players to not just a Planescape adventure, but really offering a template for people to create their own, i.e. follow intrigue in Sigil out to its logical conclusions in other planes. And while it’s nigh-unrunnable outside of the setting, that’s fine, and in fact perhaps preferable. As with the Campaign Setting, there’s little hand-holding here, and instead the expectation that everyone who plays gets involved and interested in the possibilities this strange cosmology offers.